Articles > The Montroc Avalanche

On the 9th of February 1999 the village of Montroc near Chamonix in France was hit by a massive avalanche killing 12 people in their homes. Was this a freak event in an unusual winter or something the authorities could have seen coming?

This article appeared in Volume 22 No 1 (October 2003) of The Avalanche Review - The Journal of the American Avalanche Association <http://www.avalanche.org/~aaap>

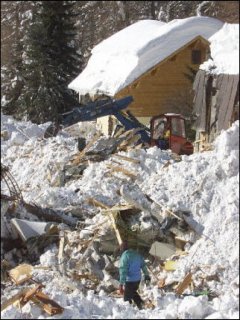

I turned off the autoroute at Martigny and under grey skies began the climb over the road pass to Chamonix. It was just a week after the massive avalanche that had hit Montroc. The low cloud, turning to mist, obscured the valley. Then, rounding a bend I was greeted by a scene of such utter devastation it was breathtaking. Forest, buildings, pylons, all smashed and broken almost beyond human recognition.

A few days later the journalist Jacqueline Meillon, in an article published in Le Parisien, raised doubts over the planning procedures followed in the Chamonix valley. It appeared that in an effort to balance development pressures in the densely populated French Alps against the risks some dangers had been overlooked. This article pieces together the chain of events that lead to the Montroc disaster.

The winter had started well with enough snowfall for many ski resorts to open early. A period of cold dry weather followed. Ideal conditions for the formation of hoar crystals and a fragile base for future snowfall. After a dry spell the snow finally arrived on the 26th of January. Well over a meter fell at la Tour, but nothing too alarming. The weather turned cold and dry again. Then the big one, on the 7th of February a deep depression crossed France. Over three days it dumped more than two meters of snow on Chamonix. In the high winds snow accumulated to worrying depths above the town. The avalanche risk was at its maximum. In the town hall the experts of the Avalanche Consultative Committee met to discuss the growing crisis. Evacuate? But where? There were over 100 known avalanche paths in the valley. Years of development under pressure from the tourist industry meant that nearly every community had some chalets at risk.

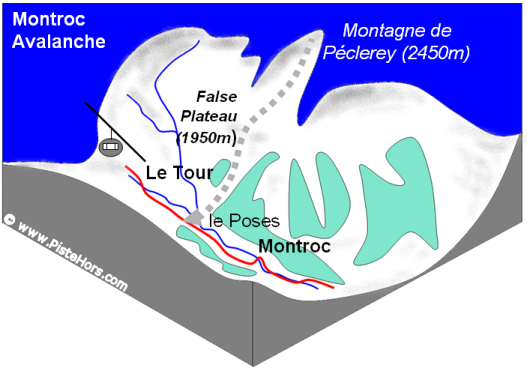

Far above the hamlet of le Poses snow had been piling up in a bowl. The valley culminated at 2450 metres at a point called la Montagne de Péclerey. At around 2:40pm on the 9th of February, while the committee discussed the situation, a slab of snow some 1.5 meters deep and over an area of 30 hectares broke away. This mass of snow started to accelerate down the 35 degree slope. At 1950 meters the slope levelled out, most winters this was enough to stop a slide in its tracks. But this avalanche was bigger, bigger than Montroc had seen for over 40 years. The slide shot past the plateau and picked up the snow accumulated on the other side. There was now 300,000 cubic meters of snow channelled directly onto the hamlet below. Nothing could resist these massive forces of nature. Travelling at 60 mph with a pressure of 5 tonnes per m2, chalets were pulverised and the debris carried over 100 meters. When the slide came to rest, 14 buildings had been totally destroyed and 6 badly damaged. The remains, and any people inside, were buried under 100,000 tonnes of snow to a depth of 5 meters. It was as if a bomb had been dropped on the whole area.

Clearing the Debris

Four years later and that bombshell is still reverberating. Michel Charlet, the Mayor of Chamonix has been found guilty of second-degree murder for not having evacuated the chalets in the 48 hours prior to the avalanche. Charlet received a 3 months suspended sentence despite a call on the opening day of the trial by the state prosecutor for the charges to be dropped on the grounds that the avalanche zoning plans were incorrect. The court stated that the Mayor is the only person responsible for evacuating houses at serious risk.

A representative for the families of the non-Chamonix victims said the verdict would remind Mayors "that they have priorities other than organising festivals, flowers and majorettes. Things have to change so that our children didn't die in vain

Before the trial Mr Charlet made these comments on the charges, Avalanche maps existed, they were wrong, since the avalanche happened at a place supposedly without risk, and I was supposed to interpret that even if there was no risk an avalanche could still happen?

Mr Charlet has decided not to appeal to permit families of the victims to receive compensation but it also means that the judgement will become part of French case law.

One of the jobs of avalanche researchers is to predict where and how often avalanches will occur. Despite sophisticated computer models and much investigation the actual mechanics of snow within a moving avalanche are still not that well understood. It is therefore important to correlate the predictions that computers provide with actual statistics from the area being studied. This lack of confidence in software means that local knowledge is still the basic tool of avalanche prediction.

Statistical modelling of the avalanche site by the French Avalanche Research Centre (ANENA) showed that the Montroc avalanche was between a 150 and 300 year event. Return periods of more than 100 years are not normally used when evaluation planning risks (Plan de Prévention des Risques Naturels - PPR) by the French authorities. Switzerland, with a longer tradition of avalanche risk assessment uses 300 year events. North America, with a much greater reliance on statistical analysis often uses even longer return periods. It should be remembered that a 150 year event does not mean that an avalanche of that magnitude will occur only once every 150 years but that there is a 1/150 chance that such an event will occur in any year. For longer periods the following formula can be used:

Probability % = 1 (1/T)L

Where T is the return period and L is the number of years. So for a thirty year period there is an 18% chance of seeing a 150 year avalanche.

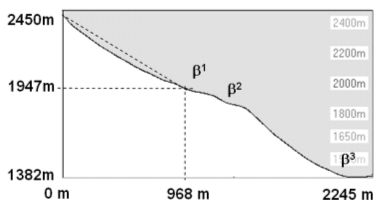

Slope Profile

The avalanche path at Montroc consists of two convex slopes. The table below gives the points where the slope angle falls to 10°, the so-called beta points. The Péclerey avalanche normally occurs as two separate slides; one starting at 2450 meters and stopping somewhere beyond β1, the second beta point can be ignored for runout calculations. It is possible that a second avalanche can start at 1700 meters.

At the end of the run the slope curves slightly upwards from the bed of the Arve river towards road and the point where the chalets were located. Although this upslope would appear to offer some protection it must be remembered that during the winter such relief would be smoothed by snowfall, especially during the exceptional conditions of February 1999. More surprisingly, the average angle from the road to the starting zone (the alpha angle) is over 25 degrees. In British Columbia this would restrict the site to lower risk highway use rather than permanent construction.

| Point | Fall | Run | Angle° |

| β1 | 503 | 968 | 27.4 |

| β2 | 589 | 1245 | 25.3 |

| β3 | 1062 | 2062 | 27.2 |

| alpha | 1060 | 2245 | 25.3 |

Table 1: Angles to Starting Point

In Europe, with its long history of habitation in the mountains local knowledge is particularly reliable. In the first century AD, the Roman poet Silius Italicus tells us that Hannibal's army were caught by a snowstorm, perhaps high on the Col du Mont Genèvre near Briançon. On the steep descent the troops were hit by avalanches. In total Hannibal lost 18,000 men and 2,000 horses crossing the Alps. Avalanche deaths became more frequent as people started to build villages higher in the mountains. Over 2,000 dead in the Rodi avalanche in Switzerland in 1618. The 1720 Galen avalanche claimed 88 lives. Although the causes of avalanches were not well understood, in 1723 the Swiss writer, Johann Scheuchzer attributed them to dragons, locals were still able to observe where avalanches happened and avoid building in those spots. Avalanches were named according to the slope or valley where they occurred. Over the centuries the safe terrain was gradually exploited and other areas left for agricultural use.

The locals at Montroc knew that the part of the valley called The Poses was prone to avalanches. Five times over the previous century an avalanche had torn down from Mount Péclerey. In 1843 and then in 1945 it had covered an area as far as the road to the village of Le Tour. The fact that it didnt come often made it no less feared. During periods of high avalanche risk locals would warn visitors not to go past Le Tomka, a chalet on the road to Le Tour.

The Avalanche Path

As the cradle of alpinism, Chamonix has been a pioneer in French efforts avalanche prediction. In 1945, the town had an avalanche map, the first of its kind in France. It describes the two avalanches at le Poses that meet on the Le Tour road, corresponding to the local knowledge at that time.

If we want to look for a single cause for the Montroc tragedy, a smoking gun, we have to return to 1970. Chamonix was growing fast under pressure from White Gold, the money from winter sports tourism as the locals called it. Maurice Herzog, then the deputy mayor was put in charge of drawing up an urban development plan (Plan dUrbanism or PUD). Herzog was a mountaineer of some reputation; along with Louis Lachenal they had been the first men to stand on the summit of an 8000-metre peak. On his return to France he had exploited this success for commercial and political purposes, something that did not sit easily with some members of the mountaineering fraternity. Montroc was one of the sites zoned for development. The 71 PUD noted the two avalanches known by the locals.

That same year a huge avalanche hit Val dIsère killing 39 people. Val d'Isère along with other resorts in France had been growing at an almost uncontrolled rate as part of the French state's plan to develop winter tourism. Buildings were constructed without receiving planning permission and, it was alleged, without proper studies of the known risks. The Val d'Isère accident was followed by deaths at Tignes and then finally at the end of the season a hospital near Chamonix was hit by a mud and snow slide claiming 72 victims of which 56 were children.

The bad publicity generated by these deaths made it nearly impossible for promoters to sell apartments in the ski stations. The development of the new resort of Val Thorens had to be put on hold. To calm public anxiety the government launched a vast project to localise the areas at risk. These maps were called Cartes de localisation probable des Avalanches or CLPA. Naturally Chamonix was chosen as a pilot project. However the CLPA for Montroc didn't record either the 1843 and 1945 avalanches. The Poses was only marked as a possible avalanche zone. The zone stopped a long way from the road and the Péclerey avalanche was shown starting lower down at 1700 and not 2450 meters. This CLPA would be the basis for subsequent zoning documents.

In light of the new CLPA, Maurice Herzog decided to revise the PUD. From February 1973 a series of meetings worked on a new document. Finally the public were invited to give their comments. Armand Charlet, a teacher at the French Ski School (ENSA) and a respected guide was strongly critical of the plan and noted that no account had been taken of "the avalanches of Grand Lanchy (Péclerey) and opposite that of d'Amont Vargnoz which covered the area as far as the Le Tour road on the 12th February 1945", he regretted that he had not been invited to the earlier meetings. "Fortunately not!" an unknown author commented in the margin, "or there wouldn't be a single plot of land worthy of construction". On the 13th of June 1973 the Town Council voted to adopt the new plan, the "importance of which cannot be exaggerated" commented Herzog, somewhat prophetically. The guide's warnings had been ignored.

This document, along with the Avalanche Zoning Plan (Plan de Zonage d'Exposition aux Avalanche - PZEA) prepared by the State Authorities formed the basis for the area development plan (Plan d'Occupation des Sols - POS). The POS was finally approved in 1979 and specified three zones:

The Poses lay largely in a white zone, the land formerly reserved for agricultural use could now be sold for development. At a much more interesting price, of course.

A year earlier, on the 2nd of February 1978 in what was practically a rehearsal for the events at Montroc, an avalanche in the Couloir de Nantet crossed the river Arve and hit four chalets at Le Tour killing five people. A court heard that although the area was zoned for construction a similar avalanche had occurred in 1966 and that the builder and town planners should have been aware of the risks.

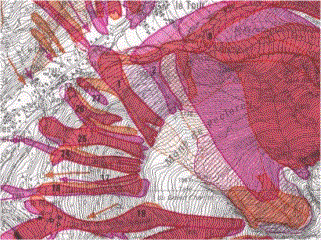

In 1991 the Cemagref revised the CLPA. This time the track taken by the Péclerey was marked as crossing the Le Tour road, as it had in the 1945 plan. The area covered on the map was almost identical to that of the 1999 accident. But neither the POS or even the Risk Evaluation Plan (PER) adopted the following year were revised.

The 1991 CLPA showing the Péclerey(1) avalanche

Eleven of the chalets destroyed in the avalanche at Montroc were built in a white zone, a sector classed as having zero risk of avalanche. A sector that was in fact known to be threatened by two avalanches. Amongst the victims were four children and a family of five from the Jura. But was building in the path of two avalanches conspiracy or cock-up?

A key actor in the drama was the agent, now dead, who prepared the 1971 avalanche plan (CLPA). Working alone, little is known about how he went about this task, whether he consulted the locals or looked at the 1945 plan. He had aerial photographs of the site, but these were unlikely to show traces of such a rare event. The subsequent town planning documents, agreed by the council, took full advantage of his revisions. However even the '71 CLPA notes the possibility of an avalanche starting from Mont Péclerey and covering the area to the road. The mayor of Chamonix, Michel Charlet states that unlike the incidents of 1970 there was no irregularity in any planning permission granted and that all the available documents (CLPA, POS, PZEA, PPR etc) were validated at a number of levels. He goes on to warn against viewing certain documents with the benefit of hindsight and notes that the Armand Charlet's comments were recorded by the CLPA but they were never communicated to subsequent Mayors.

It is possible that the councillors who approved the town plan and the locals who condoned it truly believed that big avalanches could be channelled and controlled and were a thing of the past although the tragic events of 1970 and 1978 should have been a warning against hubris. The wall of silence that reigns in the valley means that it is difficult to shed more light on this point. Danielle Arnaud's book, La Neige Empoisonnée (Poisoned Snow) talks of the strong local pressure put on officials mapping avalanches and the sudden forgetfulness of elderly land owners who would strike pay dirt if their land was zoned for construction. A young town planner who worked on the POS in the Montroc sector recalls a very strong financial pressure for development in the valley. There were indeed some doubts about the PZEA but it wasn't within their brief to revise the document.

The journalist Bernard Frédérick writing in the left wing newspaper l'Humanité refers us to the oral tradition used by the mountain folk when selecting building plots. The post war urbanism and agricultural displacement broke the chain of local knowledge passed through the generations. Frédérick also sees the change in the mountain environment as playing a role. Felling of ancient forests to build ski pistes, lifts and pylons, the developments in agriculture, can all play a role in altering the nature of, and even the areas prone to avalanche.

It seems that some locals did remember the earlier dangers. Jean-Claude Charlet, the son of Armand and an opposition councillor owns a chalet at the Frasserands on the other side of Montroc. The day before the accident he told his guests not to venture past the Becs Rouges hotel. "With time we forget about avalanches... since the 60s there has been an enormous financial pressure... today there are over 200 houses in blue zones in the valley". Michel Charlet dismisses these claims as campaigning by a political opponent. However other people were also warned of the dangers, some left for Argentière further down the valley, others chose to stay put. Amongst them, Daniel Lagarde, a specialist in avalanches who, along with his wife and granddaughter would become a victim.

Daniel Lagarde

The press has also engaged in a great deal of hyperbole about the snowfall of 1999 being a once in a century event. François Sivardière of the ANENA states that the snowfall that caused the Montroc avalanche was remarkable but not exceptional. "In 1988, 2 meters of snow had fallen over just a few days in the area and nothing happened". French Government meteorologist, Jacques Villecrose agrees that the level of snow was not the only factor. In 1999 the Mont Blanc massif was at the epicentre of events but the winter was not unique. Four other winters in the previous 30 years had seen similar levels of avalanche activity. Villecrose identifies a sequence of events, a fragile early season base which meant that any avalanche would break over the full depth and area of the snow pack. The heavy snowfall down to the valley floor meant that features that could slow the avalanche were buried. The very cold weather led to the formation of a powder avalanche. This could start spontaneously, and not due to the passage of a skier that many had assumed at the time and which led to the State Governor (Préfet) imposing a ban, albeit temporary, on off piste skiing. A powder avalanche would have the mass and speed to overcome the false plateau situated at 1900 meters and often follow paths different from norm. Slides from the summit of Péclerey generally took a route 20 to 30 degrees to the north in the direction of Le Tour.

The Memorial Cross

In the light of this information it seems that the Avalanche Consultative Committee did the best job it could in an almost impossible situation. Who would take the decision to evacuate people in a white zone when there were a good many houses in high risk areas? The avalanche itself was extremely rare, almost to the point of being unpredictable. Cemagref even draw some doubt over the extent of the 1843 slide, stating that the exact location of the Le Tour road is uncertain at that time.

As is often the case, it seems that Chamonix suffered from being the pioneers of avalanche planning, the later revisions to the CLPA show that local knowledge was eventually noted. The usual inertia in administration meant that these changes did not filter through to the planning documents. If may also have been politically difficult for the administration to remove planning permission that had so recently been granted. Landowners took advantage of these errors, the enormous development in the ski industry meant that almost worthless land now had a considerable value, by the 1970s the previous avalanche would have been a distant memory in the community. People could sell the terrain in the knowledge that the expert from the government had pronounced it safe. The fact that the dangers were not readily apparent is witnessed by the avalanche expert who stayed in his house on the day of the accident.

Four years later Im back at Montroc. Late in the afternoon in early May the village is peaceful. A small memorial cross and the concrete foundations of chalets are the only clues to the events. The mountain behind looks steep and all too close. But where in the valley isnt? The avalanche map is covered in red ink.

The winter of 1970 saw over a hundred deaths, we had to wait thirty years for another major tragedy. Over that time development in the Alps has been considerable. The measures adopted by the authorities after 1970 can be viewed as largely successful but not without errors. Will there ever be another Montroc? Probably. As long as man continues to venture into and live in dangerous areas: mountains, flood plains, in earthquake zones, there will be accidents. Despite our technology and knowledge we remain insignificant when confronted by the forces of nature.