Early season snowpack is what can turn a normal avalanche season into hell and damnation and it is something that is worth watching very closely. Last year in the Alps and Pyrenees we had a lot of snow and while avalanche deaths were up, 36 compared to a long term average of 31 the season was long, lasting from the end of October through to mid summer. Indeed the last incident was in Chamonix in mid August killing 3 climbers.The French Pyrenees, which saw monster snowfall, only had 2 deaths.

What characterized 2012/13 was a cold start to the season then good early season snowfall that bridged and insulated weak layers formed at ground level followed by consistent snowfall through the season. No repetition of the full depth slides we saw in 2011/12 and none of the carnage of 2005/6 where 55 people were killed by French avalanches.

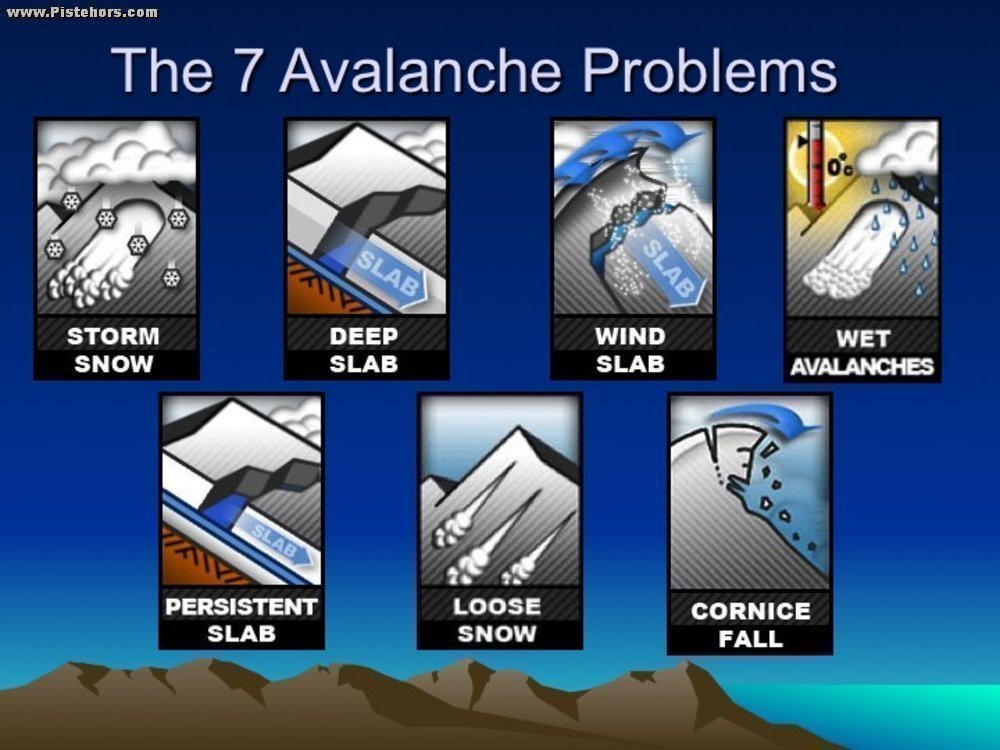

2005/2006 is a good comparison. Another very snowy winter but thin early season cover was followed by weeks of cold sunny conditions. This left widespread and hidden instabilities that caught skiers days or even weeks after any storm cycle. It is this increased randomness is the difference between a "normal" and "extraordinary" season and makes navigating in avalanche terrain hard even for experienced backcountry enthusiasts. A recent article by Don Carpenter of the American Avalanche Institute highlights the importance of early season snow-pack. He talks about the "seven avalanche problems" facing skiers and points out "that not all avalanches are created equally". Case in point, the full depth slides of 2011/12 were born in the warm autumn of that season but although they did a lot of infrastructure damage these leviathans didn't kill anyone. Keep off slopes with glide cracks and when it is warm and you are relatively safe. We need to know the snow and have a clue about the avalanche problems that we face today in the mountains.

Regular early season snowfall builds a strong snow-pack such as last year. We are then dealing with surface instabilities such as storm slabs, loose snow slides and windslab. Still deadly but we have a clue where they are hidden: close to ridge lines, on lee slopes and we can try and avoid them through route planning and manage the exposure if things go wrong (terrain traps, run-outs even using an airbag). Typically the first sunny days following a storm are the most deadly, then we can enjoy days of lower risk.

However Don cautions about seeing what we are looking for, not seeing the wood for the trees. Go out expecting a certain problem set on certain terrain and aspects and you may miss obvious clues to other types of instability and that can be a killer.

http://avalancheinstitute.wordpress.com/2013/10/28/why-do-we-follow-the-season-history/